-

Products

At homeAt workProAirthings at homeSee all products for home

Most popular

Most popular

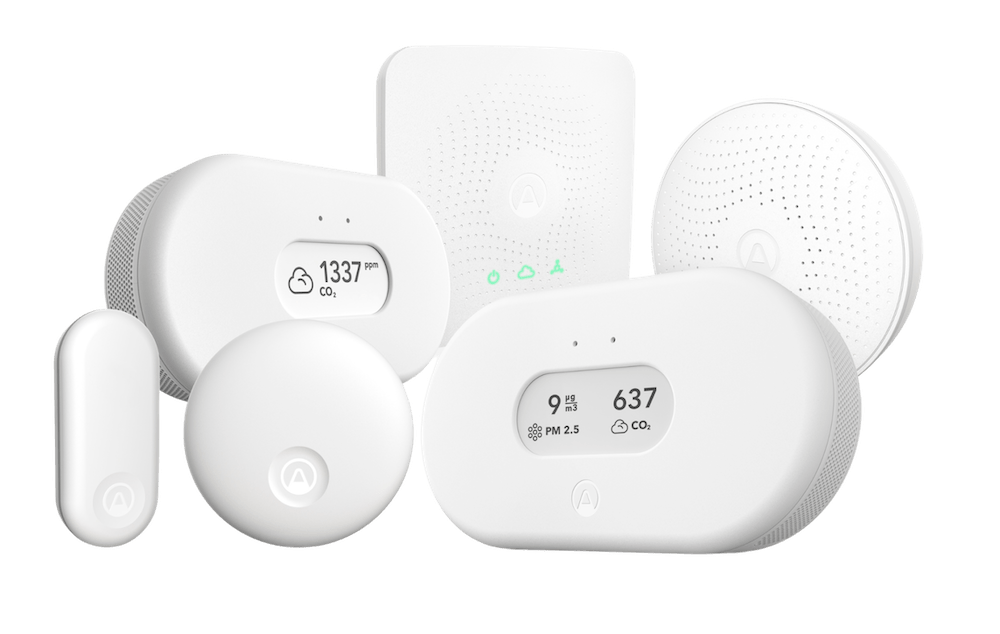

The ideal starter monitor for your home

Removes up to 99.97% of fine particles

Radon

Radon

Radon monitor trusted by professionals

Product categoriesAirthings at workOptimize building's performance, enhance workspace well-being, achieve certifications

See all solutions for work

The facility manager’s best friend.

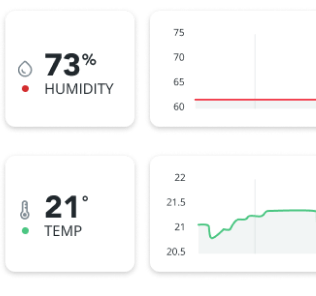

Air quality analytics.

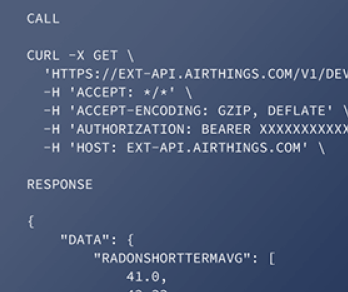

Share data between systems.

Solutions forAirthings for professionalsSee all Pro products Radon

Radon

A favorite of home inspectors and radon professionals

Radon

Radon

Services from the Airthings Lab team

Monthly and weekly rental packs

- Resources

- What is radon?